Did you know that after just three hours of sitting, your arteries can lose up to 50% of their natural dilation? This striking statistic sets the stage for what we now call Sitting Disease—a term that captures the harmful effects of prolonged inactivity on both our body and mind. In today’s fast-paced yet paradoxically sedentary world, many of us spend countless hours seated at desks, in cars, or on comfortable sofas. While our modern conveniences have made life easier, they have also paved the way for serious health concerns.

Our bodies are designed to move. When we sit for long periods, we not only burn fewer calories, but our muscles, joints, and even our brains suffer as a result. Without regular movement, our metabolism slows down, which can lead to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and a host of other metabolic disorders. Equally important, our mental health is at risk. Inactivity has been linked to increased levels of depression, a decline in cognitive function, and a general feeling of sluggishness that can affect every part of our lives.

In this article, we explore the multifaceted impact of prolonged sitting. We delve into the scientific research behind why sitting for too long is detrimental, how it affects our metabolism and mental health, and what non-exercise activities—known as Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT)—can do to help counteract these effects. We also trace the historical evolution of our sedentary lifestyle, from the industrial revolution’s factory floors to the modern office and home environments, where even leisure time is often spent sitting.

Before we dive deeper, here are the key takeaways that will guide our discussion:

- Prolonged sitting drastically reduces calorie burning, paving the way for obesity.

- Sedentary behavior is closely linked to metabolic issues such as diabetes and high cholesterol.

- Inactivity affects more than just the body; it also diminishes mental well-being.

- NEAT (Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis) plays a crucial role in counteracting the negative effects of sitting.

- Regular movement breaks throughout the day can restore energy and improve health.

This article is designed to help us all understand the real cost of sitting too much and to provide actionable steps to reclaim our health. As we move forward, we’ll share practical strategies for integrating more movement into our daily routines, whether at work or at home.

The Science Behind Sitting Disease

When we think about our bodies and their ability to thrive, movement is essential. Yet, prolonged sitting triggers a cascade of physiological changes that undermine our health. Even brief periods of inactivity can set off a chain reaction in our systems, leading to what experts now refer to as Sitting Disease.

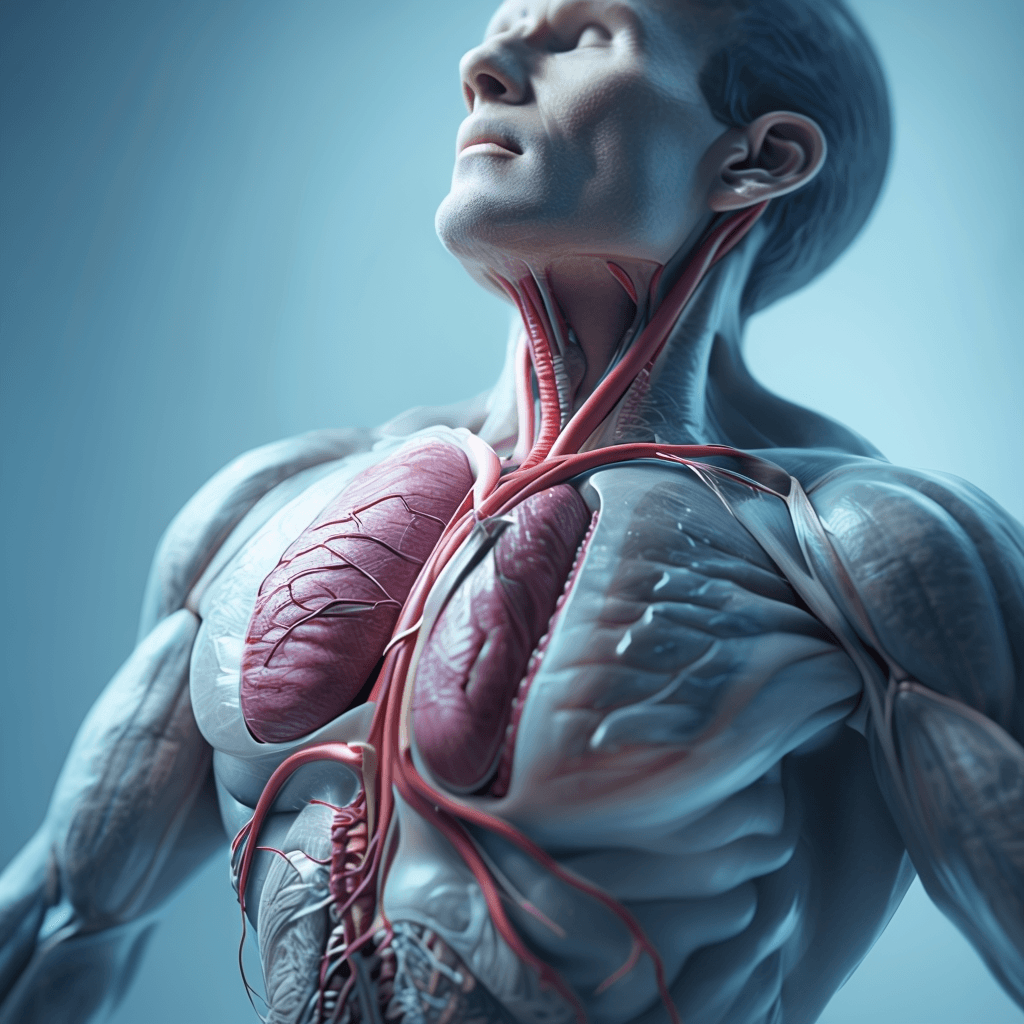

When we sit for extended periods, our muscles and arteries miss the stimulation they need to function optimally. Research shows that after just a few hours of inactivity, natural processes such as artery dilation decline significantly. For instance, studies have revealed that after only three hours of sitting, there can be a 50% drop in artery dilation. This reduction limits blood flow, placing extra strain on the cardiovascular system and compromising overall heart health. Such changes are early warnings that our sedentary habits are doing more harm than we might realize.

Moreover, our metabolism is designed to be active throughout the day. When we remain seated, the body’s ability to burn calories diminishes sharply. This metabolic slowdown leads to an energy imbalance where excess calories are stored as fat, increasing the risk of obesity. Over time, this energy deficit can contribute to serious metabolic conditions such as type 2 diabetes and hypertension. The link between reduced physical activity and these disorders highlights just how critical movement is for maintaining a healthy metabolic rate.

In addition to impacting metabolism and blood flow, prolonged sitting adversely affects muscle function. Without regular movement, our muscles are not contracted frequently enough to maintain strength and endurance. This lack of stimulation not only reduces the number of calories burned but also diminishes the effectiveness of muscle contractions in aiding blood circulation. As muscles weaken, the body’s natural systems for maintaining circulation and overall health begin to falter, further paving the way for chronic conditions.

Understanding these scientific details underscores that the act of sitting for too long is far from benign. It initiates changes in the body that affect our cardiovascular health, metabolic processes, and muscular strength. Recognizing these risks is the first step toward adopting a more active lifestyle. Below, we have summarized these key physiological effects of prolonged sitting in a concise table that highlights its impact on calorie burning, blood flow, and muscle function.

Table 1: Physiological Effects of Prolonged Sitting

| Parameter | Effect | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Calorie Burning | Reduced | Prolonged sitting decreases metabolic rate, leading to lower calorie burning throughout the day. |

| Blood Flow | Decreased | Extended inactivity results in diminished artery dilation, reducing blood flow and increasing strain. |

| Muscle Activity | Weakened | Lack of movement causes muscles to atrophy, reducing strength and joint support. |

| Insulin Sensitivity | Lowered | Prolonged inactivity impairs the body’s ability to uptake glucose, raising the risk of type 2 diabetes. |

| Arterial Health | Compromised | Diminished circulation from inactivity negatively affects overall arterial and cardiovascular health. |

By dissecting the science behind Sitting Disease, we can better appreciate the urgency of incorporating regular movement into our daily routines, ultimately protecting our bodies from the silent harms of inactivity.

Health Implications: Body and Mind

When we consider Sitting Disease, its impact extends beyond just the body. Prolonged sitting not only compromises our physical well-being but also takes a toll on our mental health. This section explores how extended periods of inactivity trigger both physical and cognitive issues, emphasizing the need for regular movement.

Physical Health Effects

Prolonged sitting leads to a cascade of adverse physical effects. When we remain seated for long periods, our metabolic rate drops, and the body’s ability to burn calories is significantly reduced. This inefficiency in calorie burning contributes directly to weight gain and obesity. Over time, these metabolic disruptions pave the way for chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol. Moreover, the lack of movement impairs circulation; blood flow slows, and arteries lose their natural dilation, placing extra stress on the cardiovascular system. This heightened strain can increase the risk of heart disease and other circulatory disorders.

Additionally, muscles that are not regularly engaged begin to weaken, affecting overall strength and endurance. Reduced muscle activity also means that joints do not receive the stimulation needed to maintain flexibility and health, which can lead to stiffness, chronic pain, and even long-term damage. The combination of these factors underlines the physical dangers of a sedentary lifestyle, emphasizing why breaking up long sitting periods is crucial for maintaining bodily health.

Mental Health and Cognitive Implications

The impact of prolonged inactivity is not confined to physical health alone; our brains are equally affected. Extended periods of sitting have been linked to increased risks of depression, anxiety, and general cognitive decline. When we sit for too long, the brain receives less oxygen and fewer neurochemicals released during physical movement—substances that are essential for maintaining mood and mental sharpness. As a result, individuals may experience a decline in their overall mental well-being, feeling sluggish or even emotionally drained.

Furthermore, regular movement is known to stimulate the production of endorphins, the body’s natural mood lifters. Without these bursts of physical activity, the brain’s ability to regulate mood and process information efficiently diminishes over time. This decline not only affects day-to-day productivity but can also lead to long-term cognitive challenges. In this way, the mental toll of a sedentary routine is as significant as its physical ramifications, reinforcing the need for movement breaks and lifestyle changes that promote both a healthy body and a vibrant mind.

The Role of NEAT

Understanding how our bodies burn calories beyond formal exercise is crucial. This is where Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) comes in—a key player in our daily energy expenditure that often goes unnoticed. By integrating small movements throughout our day, NEAT helps counterbalance the harmful effects of prolonged sitting and supports our overall metabolic health.

Definition and Mechanisms of NEAT

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) refers to the energy expended during all the activities that are not deliberate exercise. These activities include everyday actions like walking to the printer, standing while talking on the phone, or even fidgeting. Unlike structured workouts, NEAT represents the cumulative effect of our incidental movements throughout the day.

When we engage in these small bouts of movement, our bodies burn additional calories, helping to maintain metabolic balance. Even though each individual activity may not burn many calories, the combined effect over an entire day can be significant. This is especially important for those of us who spend long hours seated, as our natural calorie-burning processes are drastically reduced during extended sitting. Essentially, NEAT acts as a built-in defense against the metabolic slowdowns that contribute to weight gain, obesity, and other health issues associated with a sedentary lifestyle.

By simply incorporating more movement into our routines—such as taking short walks, standing during meetings, or opting for a few extra steps between tasks—we can activate NEAT. This activation not only aids in burning off excess calories but also helps stimulate muscle activity and improve circulation, both of which are vital for sustaining long-term health.

Research Insights and Data

Recent studies have highlighted the critical role of NEAT in managing body weight and metabolic health. Research comparing lean individuals to those with obesity shows that leaner individuals tend to have higher NEAT levels. In controlled overfeeding experiments, some participants managed to avoid significant weight gain not by engaging in intense exercise, but by naturally incorporating more movement throughout their day. These findings suggest that the secret to maintaining a healthy weight may lie in these everyday movements rather than in sporadic, high-intensity workouts.

Table 2: NEAT Levels: Lean vs. Obese Individuals

| Group | Average Daily Steps | Estimated NEAT Calorie Expenditure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lean Individuals | 7,000 – 10,000 steps | 500 – 700 calories | Higher incidental movements lead to increased energy expenditure. |

| Obese Individuals | 3,000 – 5,000 steps | 300 – 400 calories | Reduced incidental movement contributes to lower overall calorie burn. |

This table illustrates that even small increases in movement—when accumulated over a day—can result in a substantial difference in calorie burning. We see that the individuals who naturally move more not only have better metabolic rates but also enjoy improved cardiovascular health and muscle function.

In summary, recognizing the power of NEAT encourages us to rethink how we approach daily activity. Rather than relying solely on planned exercise sessions, integrating more incidental movement into our routines can be an effective strategy to combat the negative impacts of sitting. By embracing these small changes, we empower ourselves to improve both our physical and metabolic health.

Evolution of Sedentary Behavior in Modern Life

Historically, human life was defined by movement. From the early days of hunting and gathering to the physically demanding routines of agricultural societies, daily life was steeped in activity. Our ancestors engaged in tasks that required constant motion—whether it was tending to crops, constructing shelters, or traversing long distances—ensuring that both body and mind were continuously active.

The industrial revolution, however, marked a pivotal shift. As factories emerged and production lines were established, the nature of work transformed dramatically. Instead of laboring outdoors or engaging in physically demanding tasks, people found themselves confined to factory floors and later, office cubicles. This new environment emphasized efficiency over movement, with workers often required to stand or sit in fixed positions for extended periods. The very design of these workspaces began to erode the natural inclination for physical activity.

As decades passed, urbanization further entrenched sedentary habits. The rise of office jobs, coupled with technological innovations, led to a significant reduction in daily physical exertion. Commuting by car, prolonged hours at desks, and leisure activities centered around screens gradually replaced the dynamic lifestyles of previous generations. Modern conveniences—from elevators and escalators to comfortable home furnishings and readily available digital entertainment—have all contributed to a lifestyle where sitting has become the norm rather than the exception.

This evolution has not been without consequence. Research indicates that the shift toward a sedentary lifestyle is closely linked to an increased risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other metabolic disorders. The gradual transition from a movement-rich existence to a predominantly chair-bound routine has had profound implications for public health. Many of us may not recall a time when physical activity was as integral to daily life as it once was, yet the impact of this change is undeniable.

In reflecting on this transformation, it becomes clear that the human body is still fundamentally designed for movement. Our evolutionary heritage reminds us that consistent physical activity is essential for maintaining optimal health. Recognizing the historical context of our sedentary habits can empower us to reintroduce movement into our routines, whether through simple lifestyle adjustments or structured activity breaks.

Ultimately, understanding the evolution of sedentary behavior is the first step in reversing its adverse effects. By embracing the lessons of our past, we can reclaim a more active lifestyle that not only combats the negative impacts of prolonged sitting but also enhances our overall well-being.

Movement Breaks and Practical Strategies

Integrating regular movement breaks into our daily routines is a powerful strategy to counteract the negative effects of prolonged sitting. Whether at work or at home, even small bursts of activity can significantly improve circulation, boost energy levels, and enhance overall well-being. In this section, we explore practical ways to incorporate movement into our day, starting with strategies tailored for the workplace and extending to everyday life.

Simple Movement Strategies at Work

In the modern office, opportunities to move often go unnoticed. However, with a few adjustments, even a desk-bound job can become more dynamic. Consider these simple strategies:

- Stand-Up Meetings: Replace traditional seated meetings with stand-up or walk-and-talk sessions. This not only encourages movement but also promotes a more active discussion.

- Scheduled Breaks: Set a timer to remind yourself to stand up and stretch or walk every 30 to 60 minutes. Even a brief 2-3 minute walk around the office can make a difference.

- Active Desk Setups: If possible, incorporate sit-stand desks or balance ball chairs to subtly engage your muscles throughout the day.

- Walking Routes: Identify short, safe routes within your office or nearby corridors where you can take quick walking breaks between tasks.

These strategies require minimal adjustments but can lead to significant improvements in both physical and mental energy during the workday.

Incorporating Movement into Daily Life

Beyond the workplace, there are countless opportunities to add more movement into your daily routine. Here are some practical ideas:

- Commute Actively: If feasible, walk or cycle part of your commute. Even parking further away or getting off public transit a stop early can help.

- Household Chores: View everyday tasks like cleaning, gardening, or even playing with pets as opportunities to move more.

- Tech Breaks: Use breaks from screen time to perform light exercises—stretching, squats, or a brief walk around your living space.

- Social Movement: Instead of sitting at a café, suggest a walking meeting or a park stroll when catching up with friends.

Table 3: Practical Movement Break Strategies

| Strategy | Duration | Example | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stand-Up Meetings | 5–10 minutes | Replacing seated meetings with stand-up or walk-and-talk sessions. | Promotes movement and improves circulation. |

| Scheduled Breaks | 2–3 minutes every 30–60 minutes | Setting timers to remind you to take brief walks or stretch. | Prevents long periods of inactivity. |

| Active Desk Setups | Throughout the day | Using sit-stand desks or balance ball chairs. | Maintains muscle engagement and enhances posture. |

| Walking Routes | Varies | Choosing longer routes within the office or home. | Increases daily step count and overall physical activity. |

Implementing these movement strategies is not about overhauling your entire day but rather about making small, consistent changes. These brief bouts of activity, when accumulated throughout the day, can significantly offset the detrimental effects of prolonged sitting. Moreover, integrating movement into your routine can lead to enhanced mood, improved concentration, and a boost in overall productivity.

By adopting these simple yet effective practices, we can transform sedentary habits into dynamic routines. Ultimately, these changes contribute not only to better physical health but also to improved mental clarity and a more energized lifestyle.

Office and Home Environment Solutions

The places where we work and relax significantly influence our daily movement. By thoughtfully adjusting our office and home environments, we can create spaces that naturally encourage more activity and help counteract the negative effects of prolonged sitting. In this section, we explore practical solutions that support an active lifestyle in both settings.

Office Environment Adjustments

For many of us, the office is the primary setting where extended sitting occurs. A simple yet effective change is the adoption of a sit-stand desk. This allows us to alternate between sitting and standing throughout the day, which not only improves posture but also engages different muscle groups. In addition, many modern offices are incorporating treadmill desks, enabling us to work while taking gentle steps. While these tools don’t replace a full workout, they add valuable movement to our routine.

Other useful adjustments include designing workspaces that promote movement. For example, positioning common resources—like printers, water coolers, and meeting rooms—a short walk away from individual workstations can naturally prompt us to get up and move. Scheduling regular movement breaks, aided by digital reminders or timers, can also ensure that we do not remain seated for too long. Such small changes create an environment that subtly encourages us to move more frequently during our work hours, leading to improved circulation, energy levels, and overall health.

Home Setup and Lifestyle Modifications

Our home environment is just as crucial in shaping our activity levels. Even in compact spaces, we can make modifications that inspire more movement. Consider designating a specific area for physical activities, whether it’s a small yoga corner, a spot for quick exercise routines, or simply a space cleared for stretching. By creating a dedicated area, we send a strong message to ourselves that movement is a priority.

For those working from home, using a standing desk or a convertible workspace can break the cycle of prolonged sitting. Simple habits—like taking short walks during breaks, moving around while on phone calls, or even doing light exercises between tasks—can make a significant difference. Rearranging furniture to open up pathways and reduce clutter may also encourage impromptu movement, whether it’s a quick stretch or a short walk from one room to another.

By implementing these office and home environment solutions, we can take active steps toward reducing the risks associated with sedentary behavior. These adjustments are practical, easy to implement, and have a meaningful impact on our daily activity levels and overall well-being.

A Holistic Approach to Combating Sitting Disease

Understanding and combating Sitting Disease requires more than simply adding movement to our day—it calls for a holistic strategy that nurtures our physical, mental, and emotional well-being. By integrating these aspects, we can create a balanced lifestyle that not only counteracts the negative effects of prolonged sitting but also enhances our overall quality of life.

Our physical health forms the cornerstone of this approach. Regular movement, even in the form of small breaks, helps maintain muscle tone, improves circulation, and boosts metabolism. Yet, as vital as physical activity is, it represents only one facet of the solution. Equally important is addressing the mental and emotional toll that a sedentary lifestyle can impose. Incorporating practices like mindfulness meditation, deep-breathing exercises, or simply stepping away from work to enjoy a quiet moment can rejuvenate the mind and reduce stress levels. These techniques not only elevate our mood but also enhance our focus and productivity, creating a positive feedback loop that encourages further movement.

Emotional well-being, too, plays a pivotal role in our holistic health. Engaging in social activities, whether joining a walking group, participating in community events, or simply sharing a meal with friends and family, can bolster our spirits and provide the emotional support needed to maintain an active lifestyle. These interactions remind us that we are part of a larger community and that our health is intertwined with the well-being of those around us.

Nutrition and sleep are additional critical elements in this comprehensive approach. A well-balanced diet, rich in nutrients, supports our energy levels and aids in recovery, while quality sleep offers our bodies the time they need to repair and rejuvenate. When these factors—movement, mental clarity, emotional connection, proper nutrition, and restorative sleep—work together, they form a resilient framework against the effects of prolonged sitting.

Adopting a personalized strategy is key. Each of us has unique needs and challenges, so tailoring your daily routine to fit your lifestyle is essential. Start by setting realistic goals: introduce gradual movement increments, incorporate moments of mindfulness, and seek out social activities that inspire you. Remember, combating Sitting Disease is not an overnight transformation but a continuous journey toward overall wellness.

Embracing this holistic approach empowers us to transform our habits and reclaim our health. It encourages us to view movement as a natural, integral part of life—one that supports not only our physical form but also our mental and emotional vitality.

Conclusion

In summary, Sitting Disease is a modern epidemic resulting from prolonged inactivity, impacting both our physical and mental well-being. As we’ve explored, extended periods of sitting slow down metabolism, reduce calorie burning, and lead to a host of metabolic disorders such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular issues. Additionally, a sedentary lifestyle adversely affects mental health, contributing to depression and cognitive decline.

The concept of Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) highlights that small, incidental movements throughout the day can significantly mitigate these risks. Whether it’s incorporating brief walking breaks, standing during meetings, or redesigning our work and home environments, every bit of movement counts. A holistic approach—one that balances physical activity, mental stimulation, proper nutrition, and quality sleep—is key to combating the effects of prolonged sitting. By making small but consistent changes to our daily routines, we empower ourselves to reclaim vitality and foster long-term health.

FAQ

- What is Sitting Disease?

Sitting Disease refers to the health issues that arise from prolonged inactivity, including reduced metabolic rate, increased risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease, and mental health challenges. - How does prolonged sitting affect our body?

Extended sitting leads to diminished artery dilation, reduced calorie burning, and muscle weakening. This increases the risk of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and other metabolic disorders. - What role does NEAT play in our daily energy expenditure?

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) encompasses all the minor movements we make throughout the day—like walking to the printer or fidgeting—which cumulatively help burn calories and maintain metabolic balance. - What are some practical movement strategies at work?

Simple strategies include stand-up meetings, scheduled short breaks to walk or stretch, and the use of adjustable sit-stand desks to reduce continuous sitting time. - How can home environment adjustments help reduce sedentary behavior?

Creating dedicated spaces for movement, using convertible workstations, and even rearranging furniture to encourage short walks or stretches can significantly lower the amount of time spent sitting. - How does prolonged sitting affect mental health?

Sitting too long can lower the production of mood-enhancing endorphins, leading to feelings of sluggishness, increased stress, and a higher risk of depression and cognitive decline. - What holistic approaches can help combat Sitting Disease?

A holistic approach combines regular movement, mindfulness, social interaction, balanced nutrition, and quality sleep. Tailoring these elements to your lifestyle fosters overall well-being and counters the negative effects of prolonged sitting.

Sources and References

The following sources provided valuable insights into the health impacts of prolonged sitting, the role of Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT), and practical strategies for reducing sedentary behavior. These links include evidence-based studies, reputable health publications, and government guidelines:

- Harvard Health Publishing – Sitting Disease:

The dangers of sitting

An in-depth look at the health risks associated with prolonged sitting and the emerging concept of Sitting Disease. - Mayo Clinic – The Dangers of Prolonged Sitting:

Sitting risks: How harmful is too much sitting?

A comprehensive overview from a trusted medical institution on how extended periods of inactivity can lead to serious health issues. - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – Physical Activity Guidelines:

CDC Physical Activity Basics

Essential guidelines and recommendations for incorporating physical activity into daily routines to combat the risks of a sedentary lifestyle